Redirection: How Catalogs Create Demand For Online Pureplays

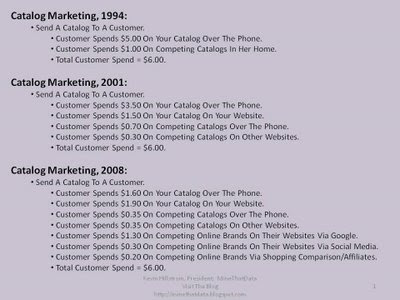

Given that catalogers seem to enjoy yesterday's discussion about the failure of catalog and multichannel marketing, is is appropriate to share the following outline concerning demand generation in 1994, 2001 and 2008. Of course, what follows in the image is only a theory of mine --- no hard evidence to prove one way or another. Click on the image to enlarge it.

My theory suggests that catalog marketing is as effective as it has ever been. However, Google and Social Media have stepped in and redirected demand that would have gone to your brand.

Redirection (otherwise known as "transfer" in Multichannel Forensics) happens in many different ways.

- Google and SEO --- think about how many of you found my blog via Google/SEO?

- Google and Paid Search.

- Social Media --- Check out Manolo's Shoe Blog as an example.

- User Generated Reviews --- You see an item advertised in the Crutchfield catalog, you read a review from a customer on Amazon.com, and you ultimately buy the item on Amazon instead of Crutchfield.

This theory suggests that we have two important objectives.

- Prevent redirection of demand away from our brand.

- Induce redirection of demand to our brand.

Abacus/Epsilon --- what do you think? You could so easily help the catalog industry that pays your freight by generating an index of this nature for your clients. There you go, free product development information from The MineThatData Blog! You've got bright people, make something happen! Heck, toss me a few pennies, and I'll develop the prototype.

Too often, we view the world through tactics, like catalog marketing or e-mail marketing or paid search or SEO or affiliate marketing. How often do we view the world in the context of "redirection"? How might we approach competitive advantage via the concept of redirection?

Labels: Abacus, Amazon.com, Crutchfield, Footsmart, Multichannel Forensics, Redirection, Transfer Mode, Zappos